See full artwork here: Libyan Sibyl. Oil, 2018.

Libyan Sibyl (2018)

In 2018 I painted a copy of Michelangelo’s Libyan Sibyl. The idea came to me in May of that year, but the true genesis of this project can be traced back to the summer of 2011. That was when I first laid eyes upon the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

I was on a family trip, at the tail end of a tour of the Vatican. We’d walked through many rooms and halls, past priceless paintings, tapestries, and sculptures from around the world, dating back to antiquity. A set of small corridors leads you to the grand finale of your visit, the Sistine Chapel, and as you enter, your eyes are magnetically drawn up to the fresco above you:

The ceiling, painted by Michelangelo from 1508-1512, depicts the Book of Genesis–the Biblical story of God’s creation of the world, mankind’s fall from Paradise, and its eventual salvation.

Here I was almost 500 years later, looking up at it in complete astonishment.

I thought about what it must have taken for one man¹ to produce this work: the creative vision to conceive of such a grand project and the tireless devotion and technical mastery required to bring that vision to life… To this day it still amazes me to think, someone painted that:

People create art for many reasons – to entertain, provoke, question, or simply to create something that looks cool or beautiful. I personally think art is most impactful when it inspires. This was one of the hallmarks of Renaissance art.

The Renaissance (15th-16th c.) was a period of cultural rebirth in art, philosophy, science, and literature centered around humanist ideals from Ancient Greece and Rome. It was characterized by intellectual inquiry, individualism, and moral autonomy. People were interested in the question of what it means to be human.

Artists began centering their works on the human experience and leveraging mathematical techniques to achieve a degree of realism that was theretofore impossible. This involved using linear and aerial perspective to convey depth, and scientific proportions to accurately depict the human form.

The mastery, style, and influence of the period culminated in the High Renaissance, which was helmed by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raffaello Sanzio (a.k.a. Raphael) all at the peak of their powers. The Sistine Chapel was the epitome of this brief golden age.²

Merely seeing it with my own eyes left an indelible mark on me: it spurred a deeper study of Art History and a return to Italy the following year (2012); it led to a fascination with the aforementioned masters (Michelangelo in particular) whose works I studied and copied.

Most importantly, it made me question what a human being was truly capable of, for this is more than just a work of art: it is a testament to human ingenuity, the willingness to dream big, and the pursuit of perfection.

As Michelangelo himself said: “The greater danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.”

⬩⬩⬩

Fast forward to the spring of 2018. I had quit my job abroad and moved back home. Four years since graduating from college had passed in the blink of an eye. I’d spent that time working and learning as much as I could, but I felt I needed to make a change. So, I moved home to figure out precisely what that change should be.

What ensued was a period of introspection and exploration. I spent time on activities that brought me joy, and made space for the answers I had been seeking to come. One of these activities, of course, was making art.

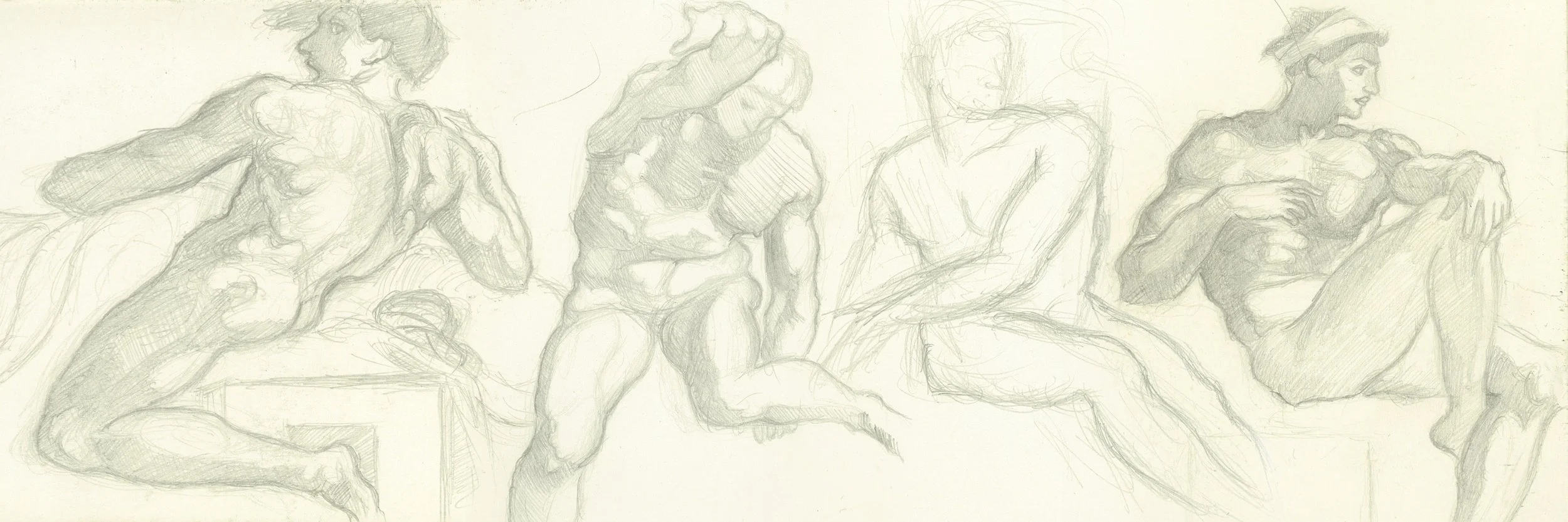

One day, while thumbing through my old sketchbooks, I stumbled upon sketches I’d made of the Ignudi (below) that Michelangelo painted on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling. The ideas discussed above struck a chord once again. I decided that my next piece would be an homage to this work that had so greatly inspired me.

I looked at the ceiling’s various panels and before long found my muse in the Libyan Sibyl. Graceful, dynamic, and vibrant, this scene (below) features a wonderful interplay of colors and textures–from the rosy skin and flowing drapery, to the stony architectural niche framing the central action.

The composition is rich and interesting. The figure is depicted mid-action as she simultaneously closes the book behind her and steps down towards the viewer. The Libyan Sibyl is part of a larger narrative that unfolds across the ceiling, but compositionally this scene has a completeness that enables it to stand on its own.

The Libyan Sibyl was an oracle in Ancient Greek mythology, and the book is a symbol of wisdom and the ongoing pursuit of knowledge–ideas which are representative of the Renaissance era. Everything about the Libyan Sibyl felt ‘right’. It was aesthetically appealing, deeply symbolic, and personally meaningful.

⬩⬩⬩

By 2018 it had been almost 10 years since I’d worked on any type of painting, and I’d never made one this complex. I had been harboring feelings of insecurity, feeling that I couldn’t call myself a true artist if I wasn’t able to paint (pencil had always been my preferred medium).

Note: the notion that one need to paint in order to be considered an artist is utter nonsense, but this was the nature of inner dialogue at the time.

Despite my anxieties, the thought of this project was incredibly exciting. So, I bought a 30 x 30” canvas from my local art store and got to work.

This painting took several months to complete. On some days I didn’t touch a paintbrush, while on others painting was all I did. In the final stages, I would work until the early morning in a state of feverish excitement. It was some of the most fun I’ve ever had, bar none.

The final strokes were applied on October 26, 2018. After the painting fully cured, it was varnished and framed. Today, my version of Libyan Sibyl hangs at home in Toronto.

After completing this painting, I felt much more confident in my ability to confront new challenges–both artistically and beyond. The answers I’d been searching for came eventually, and today I look back on this brief chapter fondly.

When I walk past it today, I am reminded of Michelangelo’s important lesson: that our only real limitations are those which we impose on ourselves.

Footnotes

Michelangelo had assistants to help construct scaffolds, purchase pigments, and transfer his drawings to the wet plaster, but he was the only one to apply brushstrokes to the fresco itself.

It must be noted that the Sistine Chapel has other artworks (including tapestries by Raphael and an altar wall fresco, also painted by Michelangelo) that have contributed to its world renowned fame. That said, its iconic ceiling is the most exceptional.